Santoor

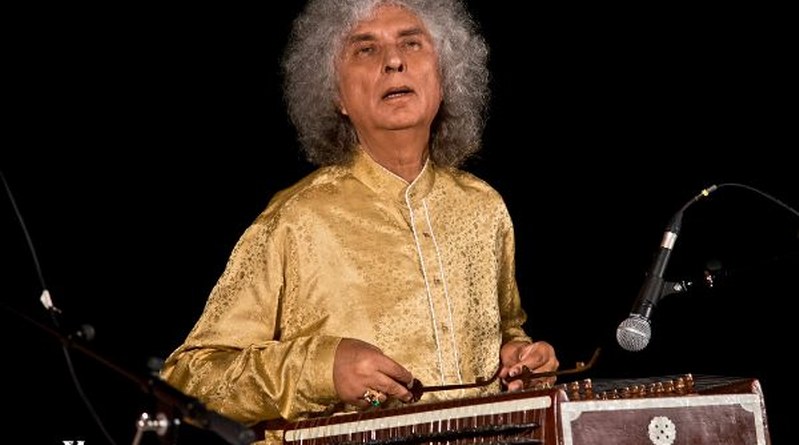

A music instrument so old that its roots can be traced back to Rigveda, ancient Indian scriptures that are almost 4000 years old, yet most people in India had never listened to it till as recent as 50 years ago. An instrument so finicky that one has to sit with legs crossed and back straight for hours to be able to play it correctly or it won’t sound perfect. And it's also an instrument that when you listen to it, you reach a calm, almost meditative state and you even forget to clap after the performance is over, as what happens when Pt. Shivkumar Sharma, a name synonymous with the instrument itself, plays Santoor.

Tracing its roots to Pinaki Veena mentioned in Rigveda, Santoor gets its name from Shat Trantri Veena. “Shat” means hundred and “Tantra” or “Tar” means string. So, this is a one hundred string musical instrument and the name became from Shat-tantri to Shat-tar to San-tar to Santoor. The instrument itself is a large trapezoidal box that is hollow from inside that allows sound to resonate. This is the same principle as almost all other string instruments such as Sitar or Veena or even Guitar have. While being a very old instrument, why did Santoor disappear from the India classical music?

In Santoor, one hundred strings are mounted over twenty-five bridges from the left side of the box to the right side with four strings on each bridge. The sound is created by tapping the string with a soft wooden mallet versus using plucking of the string as in many other string musical instruments. Each string creates a different note when tapped and many things determine the sound that is produced such as the width of the string, tension in the string, amount of hollow space in the box below the string, where the string is tapped and how hard or softly it is tapped. For anyone who has played guitar can attest that controlling the sound from a four or six string Guitar is very hard. It requires adjustment of tension on the string from time to time - a process known as tuning. For Santoor, this process is 10X more complex because of the number of strings involved.

Was it the complexity in managing sound quality from a Santoor that led to its disappearance from Indian Classical music? Actually, the answer is more complex. Santoor has a wide variety of notes that can be produced because it has one hundred strings but each note is a distinct note. It’s almost like typing on a keyboard. You press letter A and an alphabet ‘A’ gets printed on the screen. If you press ‘B’ then a different alphabet ‘B’ gets printed. While Santoor has 100s of alphabets but these are all distinct alphabets or notes as we can call it for music. Indian classical music system has its base in vocal sounds and many of the music compositions, also known as Ragas, in India classical music require a smooth transition between notes. It’s almost like a painting versus typed text. Colors in a painting seem to blend into each other and one can’t tell where one color ends and the other one starts. Similarly, in Indian classical music, an artist transitions from one note to another in a gradual way and it was not possible to create such transitions on Santoor, a musical instrument that has one hundred distinct notes. So, performers adopted string musical instruments that can be plucked such as Sitar and Sarod and non-string instruments such as Flute and Shehnai that are much more capable of producing such transitions.

But the sounds produced from Santoor are exceptional and the variety of notes it can produce provided so much flexibility to a performer that the instrument lived on outside of Indian classical scene and adopted by Gypsies. It eventually found its way to Persia and it was used in devotional Islamic music known as Sufiana music. Santoor was mostly used to provide background music for vocal Sufi music and very rarely it was used in solo performances. But that was about to change when Pandit Umadatt Sharma, who was in charge of Radio Srinagar in Kashmir valley in the early 1950s, and an accomplished musician himself, decided to use the instrument for Indian classical music. Pandit Umadatt had taken his music lessons from Pandit Bade RamdasJi of Benaras Gharana and being a vocalist himself, he knew the challenges in using Santoor for India classical music. Humans have shown exceptional creativity throughout history and Pandit Umadatt’s experiments with Santoor were along the same lines. He started experimenting with the instrument and also started teaching his son who would become the legendary Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, how to play this new instrument. Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma’s experiments continued for several more years. He increased the number of bridges from 25 to 26 to 29 and eventually to 31 to get the range of notes required. He reduced the number of strings per bridge from 4 to 3 to save tuning time and settled at 91 strings total. He even experimented with metals and alloys used as strings and developed techniques such as holding the fret in a certain way and gliding it over multiple strings to be able to play Indian classical music on this amazing instrument. After giving a performance to Indian classical music enthusiasts at a young age of 16, Pandit Shivkumar Sharma published an album “Call of the Valley” when he was only 29 years old and this became one of the most successful Indian music albums of all times.

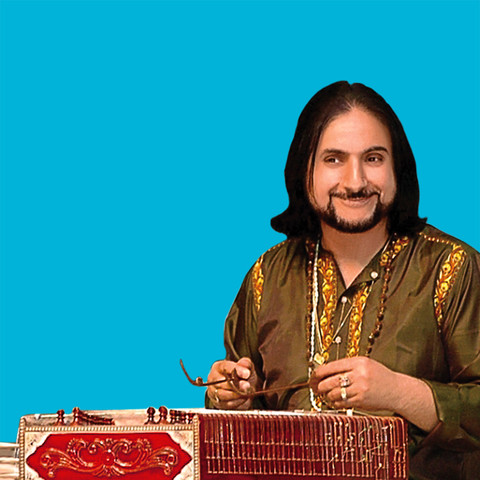

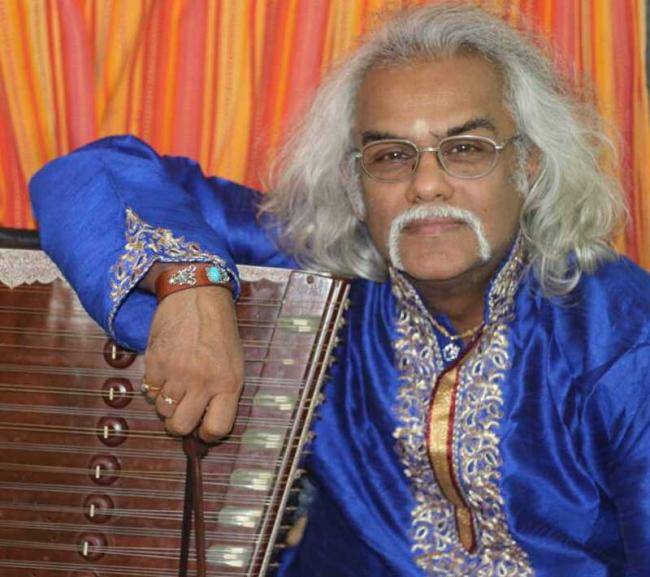

While Pandit Shivkumar Sharma is credited with bringing Santoor to mainstream Indian classical music scene, a few other noteworthy performers have contributed equally. Pandit Bhajan Sopori who is a contemporary of Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma and about 10 years younger also did experiments on Santoor to be able to play Indian classical music. Interestingly Pandit Bhajan Sopori also hails from Srinagar and comes from a family of legendary Santoor players but they all played Sufi music on it. Like Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, Pandit Sopori increased the number of bridges and developed techniques for holding and gliding frets. His Santoor has a different number of bridges and strings from Pandit Shivkumar Sharma’s Santoor but Pandit Bhajan Sopori has also successfully established Santoor for playing Indian Classical music. About 2000 km away in Bengal, Pandit Tarun Bhattacharya, a disciple of none other than Sitar maestro Pandit Ravi Shankar, also experimented with Santoor and he developed techniques for tuning the instruments easily. On the west coast of India, Pandit Ulhas Bapat experimented with Santoor and made it an instrument of choice for Indian film music by playing the instrument for legendary R.D. Burman’s songs.

With the efforts of many exceptional musicians, who have devoted their lifetime in mastering this complex instrument, Santoor has found its place in the Indian classical music and its magical notes have touched the hearts and souls of many fans all over the world.